Wildfire is a catalyst: it rapidly changes the landscape, and also changes us. The artwork presented distills research into imagery to reflect on the human relationship with wildfire. How do we learn to coexist with fire and be best prepared to respond to it? This collaboration explores issues of slow decadal environmental and social changes such as warming temperatures, trajectories of tree growth and mortality, and expanded residential development into wildlands, intersecting with rapid increases in wildfires across the Colorado landscape.

Wildfires have been increasingly impacting Colorado communities in recent years as burning conditions have become hotter, drier and last longer. The work in this exhibition is inspired by interactions with these communities affected by wildfire and investigates how we might learn to better coexist with wildfire in the future.

How do we learn to coexist with fire and be best prepared to respond to it?

Art, Science, Place, and Community

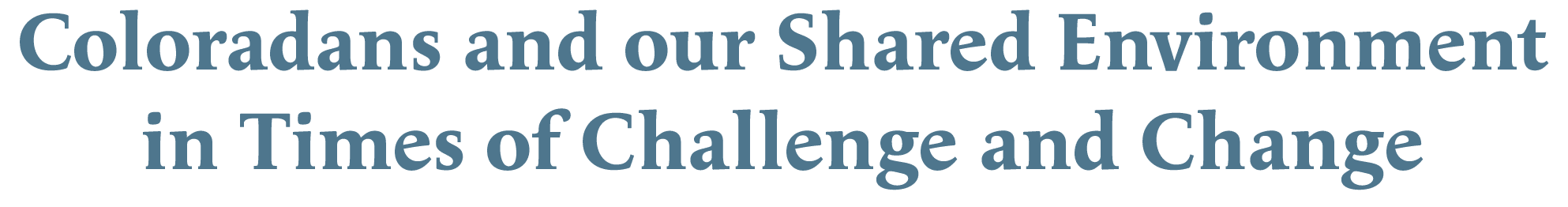

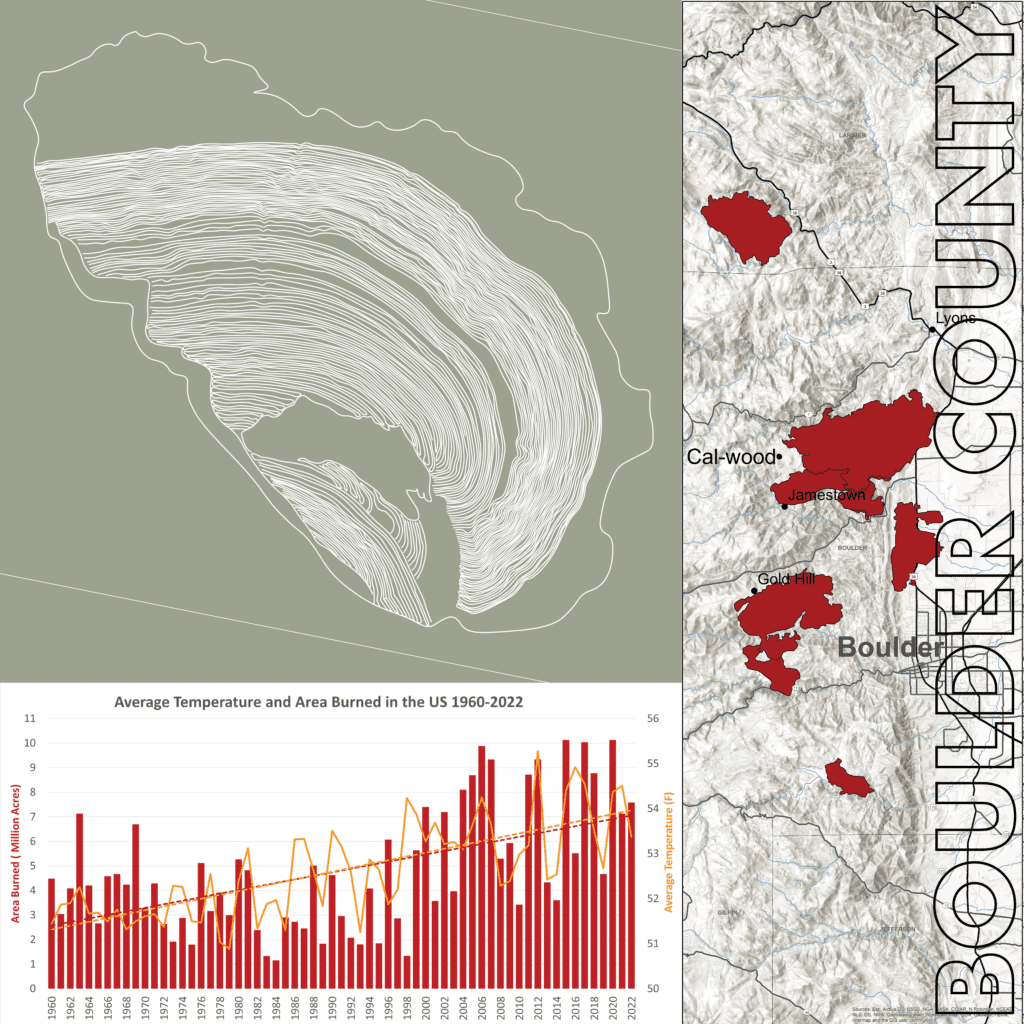

This work was created from a collaboration between landscape ecologist Tania Schoennagel and artist Amy Hoagland. The artwork invites us to consider a changing Colorado landscape and to explore how such changes may affect, reflect and inspire us. The artwork incorporates historical and contemporary aerial imagery of forest change, tracings of a fire-scarred tree used by scientists to reconstruct fire history and published scientific papers addressing human resilience with wildfire. Aerial imagery and fire history data from Boulder County reflect examples of landscape change, risk and resilience. Hoagland reached out to community members asking a series of questions about experiences related to wildfire and created educational programming for the Cal-wood Education Center in Jamestown, CO. This work is interested in shifting community perspectives towards more positive and proactive relationships to wildfire.

What you can do to address this issue

In terms of adaptation to wildfire, here’s what we can do to better protect ourselves and our neighborhoods from destructive wildfire:

- Reduce human-caused ignitions where we live (see Climatecheck.com How do Wildfires Start);

- Harden your home against wildfire (see Readyforwildfire.org,Building a Wildfire-Resistant Home, Wood roof mitigation, Fema.gov);

- Design fire-adapted communities (see Firetopia Land Use Planning , Fire Adapted Communities);

- Seek homeowner or rental insurance that covers wildfire damage (see state of Colorado homeowners/renters information);

- Make an inventory of belongings (see How to Create a Home Inventory);

- Be disaster ready

- Get involved, volunteer with forest restoration (see Wildlands Resoration Volunteers, Volunteer Colorado Forests, Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado and Volunteer at Cal-wood Education Center).

References

Environmental and Social Issues

This collaboration explores how slow environmental and social changes over decades (e.g., warming, changes in forest density, and expanding residential development) intersect with rapid recent increases in wildfires across the Colorado landscape. Wildfire is a catalyst. It rapidly alters the landscape and also changes us. Our work encourages the viewer to reflect on their relationship with wildfire and to feel urgency and agency. With wildfires increasingly affecting the built environment, communities are having to learn how to coexist with wildfires.

Science Integrated into the Artwork

Fire-prone ecosystems in Colorado have experienced complex changes that reflect our human fingerprint. Since the 1970s, Colorado is 2⁰ F warmer, fire seasons are three months longer and protective snow is melting earlier. As a consequence, twenty of the largest wildfires on record have all occurred since 2002, an increasing number of burned forests are converting to grasslands or shrublands that store significantly less carbon, and tree mortality is increasing (see references below). Expansion of residential development into wildlands is co-occurring with more human-ignited wildfires and a significant increase in home destruction by wildfire (as shown in these references: wildland-urban interface, mdpi.com and here).

Recent changes in fire and forests are occurring across a landscape with long fire and forest histories. For example, in low-elevation forests, frequent low-severity fires were common, but fire suppression over the last 100 years allowed young trees to fill-in previously sparse forests, leading to uncharacteristically dense forests and severe fires today. In contrast, in high-elevation forests, relatively infrequent high-severity fires burning naturally dense forests remain largely unchanged.

Thinning trees to reduce fuels and the severity of forest fires seems like an intuitive solution to slow the spread of wildfires, but it has significant limitations in keeping communities safe. Few tree-thinning projects actually encounter wildfires due to the scale of fire-prone ecosystems. Most of the area burned across the U.S. is in grasslands, and most homes ignite via ember showers where home loss correlates with fuels directly around the home. Forest management has a place in Colorado landscapes, but it isn’t a simple solution to our complex wildfire problem. While Colorado landscapes and wildfires have changed in many ways that reflect our human footprint, wildfires are also changing us, inviting us to adapt in creative and effective ways.

The artwork shown above is located in the Colorado State Capitol through October 16, 2023.